The decision to undergo aesthetic enhancement—whether through minimally invasive procedures like injectables or more transformative surgery—is rarely a simple calculation of physical change. It is a profound psychological journey, shaped by the intricate interplay between our internal self-perception, the powerful external forces of social media and culture, and the complex emotional aftermath of the procedure itself. To view aesthetic treatments as merely physical alterations is to miss their true significance; they are interventions into identity, acts of self-creation fraught with hope, anxiety, and the deep-seated human desire for social belonging. This article delves into the psychological underpinnings of aesthetic enhancement, exploring the foundations of self-perception, the formidable influence of social media, and the multifaceted nature of post-treatment satisfaction.

The Architecture of Self-Perception: Why We Seek Change

The drive toward aesthetic enhancement originates in the complex and often fragile relationship we have with our own image. This self-perception is not a perfect reflection in a mirror, but a distorted picture filtered through cognitive biases, emotional states, and lifelong experiences.

Body Image Dysmorphia and the “Zoomed-In” Lens: For some, the pursuit of enhancement is pathologized as Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD), a condition characterized by a preoccupation with a perceived flaw that is minor or nonexistent to others. However, a less extreme but more common phenomenon is what can be termed “aesthetic hypervigilance.” In an era of high-definition front-facing cameras, individuals become hyper-aware of minute facial asymmetries, texture, and lines that were once invisible in the fleeting reflections of daily life. This constant, pixel-level self-scrutiny creates a distorted self-perception where individual features are magnified and the holistic face is lost, fueling the desire for targeted correction.

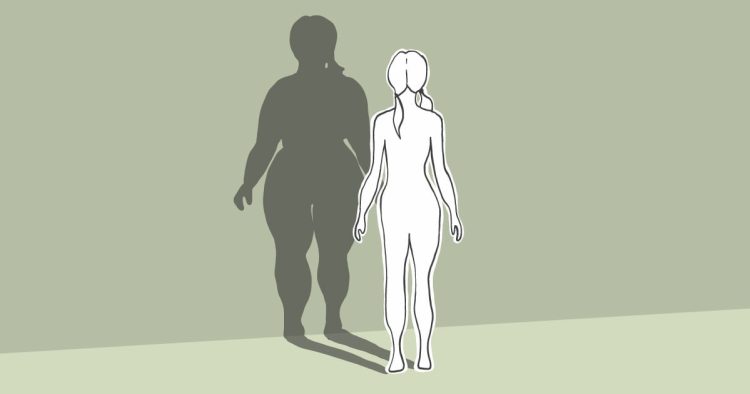

The “Mismatch” Theory: Aligning the Outer Self with the Inner Self: A powerful psychological motivator is the feeling of an internal-external mismatch. A person may feel vibrant, energetic, and youthful internally, but perceive their face as telling a story of fatigue, aging, or sadness that does not align with their self-concept. Aesthetic enhancement, in this context, becomes a tool for reconciliation—an attempt to sculpt the external vessel to better represent the internal reality. This is not merely about “looking younger,” but about looking more like oneself as one feels inside.

Agency and Control in an Unpredictable World: The aging process can feel like a loss of control. Gravity, sun exposure, and genetics enact their changes relentlessly. Opting for an aesthetic procedure is, psychologically, an assertive act of reclaiming agency. It is a declaration that one can intervene in a natural process, shaping one’s own narrative of aging and appearance. This sense of control can be profoundly empowering, contributing to improved self-efficacy and overall well-being, independent of the physical outcome.

The Social Media Mirror: Curated Worlds and Comparison Culture

If self-perception provides the internal catalyst for change, social media provides the external blueprint and the relentless pressure to conform. It has fundamentally altered the landscape of aesthetic desire, normalizing enhancement and creating new, digitally-native beauty ideals.

The “Filter First” Phenomenon and Shifting Baseline Syndrome: The widespread use of augmented reality (AR) filters has created a novel psychological phenomenon. Individuals become accustomed to seeing a digitally altered version of themselves—with smoothed skin, enlarged eyes, and sculpted jawlines—in their daily video calls and social media posts. This “filtered self” becomes the new mental baseline for one’s own appearance. The real, unfiltered face in the mirror begins to look abnormal or deficient by comparison. This creates a direct pathway to the clinician’s office, with patients bringing screenshot of their filtered selves as reference points, seeking to make their reality match their digital avatar.

The Normalization of the “Tweakment”: Social media platforms, particularly TikTok and Instagram, have democratized and de-stigmatized aesthetic procedures. Influencers and everyday users openly document their journeys with Botox, filler, and lasers, using casual terms like “tweakments.” This constant exposure normalizes what was once a taboo subject, embedding it into mainstream self-care routines alongside skincare and fitness. The narrative shifts from one of vanity to one of proactive “maintenance” and “self-improvement,” making the psychological barrier to entry significantly lower.

The Algorithmic Narrowing of Beauty Standards: Paradoxically, while the internet offers access to global diversity, social media algorithms often create homogenized beauty standards. By showing users content that generates the most engagement, these algorithms reinforce a specific, narrow ideal—often characterized by a hyper-smooth complexion, high cheekbones, full lips, and a defined jawline. This “Instagram face” becomes a universal, cross-cultural benchmark against which individuals measure themselves, eroding cultural-specific beauty ideals and creating a globalized, often unattainable, standard that fuels widespread body dissatisfaction and the pursuit of standardized procedures.

The Emotional Aftermath: The Complex Terrain of Post-Treatment Satisfaction

The psychological journey does not end when the procedure is complete. The period that follows is critical, where expectations collide with reality, and a new self-perception must be integrated.

The “Post-Procedure Paradox” and Adjustment Period: Many patients experience a period of emotional volatility immediately following a procedure, often termed the “post-procedure paradox.” Even with a technically successful outcome, the sudden alteration of a familiar feature can trigger a temporary identity crisis. The face in the mirror is both “me” and “not me.” This requires a psychological adjustment period where the brain must update its internal self-image to match the new external reality. Supportive clinicians now often provide “emotional consent,” preparing patients for this potential phase of unease or “buyer’s remorse” that typically resolves as they acclimatize.

The Discrepancy Between Technical Success and Psychological Satisfaction: A result can be technically perfect from a clinical perspective—symmetrical, natural-looking, and achieving the stated physical goal—yet leave a patient feeling unsatisfied. This disconnect highlights that satisfaction is not solely dependent on the objective result, but on a complex interplay of factors:

- Met Expectations: Were the patient’s expectations realistic and clearly communicated? Unrealistic hopes for a procedure to solve life’s problems (e.g., “If I get a rhinoplasty, I’ll find a partner”) inevitably lead to disappointment.

- The Role of Pre-existing Mental Health: Underlying issues of depression, anxiety, or low self-esteem are not resolved by a cosmetic procedure. If a person seeks treatment to “fix” their self-worth, the underlying psychological void will remain, leading to dissatisfaction and potentially a cycle of repeated procedures (“poly-surgery”).

- Social Feedback: The reactions (or lack thereof) from friends, family, and colleagues can profoundly influence a patient’s satisfaction. Positive reinforcement can validate the decision, while negative or critical comments can trigger regret, even if the patient was initially happy.

The Pursuit of the “Unseen” Result: The most profound psychological benefits of aesthetic enhancement are often the most subtle. It is not about receiving compliments, but about the cessation of negative self-talk. The satisfaction comes from no longer being preoccupied by a specific feature, from feeling that the internal-external mismatch has been reduced, and from the quiet confidence that comes from no longer feeling the need to hide or compensate. This “unseen” result—the liberation from self-critical thoughts—is a powerful indicator of deep psychological success, yet it is rarely captured in before-and-after photos.

Conclusion

The psychology of aesthetic enhancement is a rich tapestry woven from threads of identity, social pressure, and the profound human need for agency. It reveals that the scalpel, the needle, and the laser are not just tools for modifying tissue, but instruments that interact with the most intimate parts of the human psyche. The consultation room is, therefore, as much a psychological space as a medical one, requiring practitioners to be not only skilled technicians but also empathetic listeners and ethical guides.

As these procedures become increasingly normalized, the imperative for psychological literacy grows—for both providers and patients. A successful outcome is not merely a physical metric but a holistic one, measured by the alignment of outer appearance with inner self, the management of expectations, and the ultimate enhancement of psychological well-being. In understanding the deep-seated motives and emotional consequences of this journey, we can foster a more ethical, compassionate, and ultimately more satisfying approach to the art and science of aesthetic enhancement.