Aesthetics, often associated with beauty, has traditionally been confined to the realm of visual pleasure. The word itself originates from the Greek word aisthesis, meaning “perception” or “sensation.” However, as the world of art, design, and philosophy expands, so too does our understanding of aesthetics. In this article, we will explore how aesthetics can be redefined beyond the confines of mere visual pleasure, incorporating a broader understanding that spans the auditory, tactile, conceptual, and emotional dimensions.

1. Reexamining Aesthetics: A History of Visual Dominance

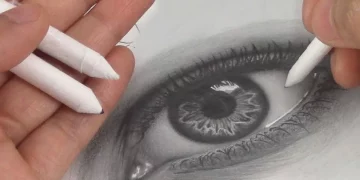

For centuries, aesthetics has been largely tied to the visual experience. From the classical art forms of the Renaissance to the hyperrealistic portrayals of the 19th century, the visual appeal of an object or artwork was often the main criterion for its aesthetic value. Think of the Grand Tour, where the elite class traveled across Europe, not just for knowledge but to immerse themselves in the visual grandeur of art, architecture, and natural landscapes.

But as times have changed, so have the ideas surrounding beauty and pleasure. Philosophy, particularly in the works of Immanuel Kant, has traditionally tied aesthetic value to the pleasure derived from visual beauty. Kant proposed that aesthetic judgment is based on a disinterested pleasure, free from personal interests or practical concerns. In this narrow view, only visual experience was deemed worthy of aesthetic contemplation.

Yet, this paradigm is being increasingly questioned. In modern times, new fields such as design, music, architecture, and even digital experiences have stretched the boundaries of what can be considered aesthetic.

2. The Auditory Dimension: Sound as Aesthetic Experience

One of the most significant ways in which aesthetics can transcend the visual is through sound. The world of music, for instance, provides a rich tapestry of aesthetic experiences, none of which depend on visual stimuli. While it is true that certain genres of music, such as opera, often involve a visual component (stage, costumes, etc.), the core of the experience is auditory.

Imagine standing in a concert hall, the sound of a symphony orchestra filling the room. The resonance of strings, the warmth of brass, the delicacy of woodwinds, and the rhythm of percussion form an intricate auditory landscape. In this case, the aesthetic experience is centered entirely on how sound interacts with the listener’s emotions and physical sensations, without any reliance on what is seen.

The concept of auditory aesthetics extends beyond traditional music. The sound design in movies, video games, or even architectural spaces can create profound aesthetic experiences. The rustling of leaves in a forest, the hum of a city street, or the calming sound of waves crashing on a shore—these are all examples of auditory aesthetics that shape our perceptions and moods.

Case Study: The Aesthetics of Silence

Silence itself can be considered an aesthetic experience. The minimalist works of John Cage, such as his famous piece 4’33”, challenge the conventional notion that music must be full of sound to be aesthetically valuable. Cage’s piece, where performers remain silent for four minutes and thirty-three seconds, invites the audience to focus on the ambient sounds around them, turning the concept of silence into an art form. This is a stark reminder that aesthetics are not solely about what we see or hear directly; they also involve how we perceive and experience the world around us.

3. The Tactile Dimension: Aesthetic Experience Through Touch

While sight and sound have long been the dominant modes through which we experience aesthetics, touch offers another powerful, yet often overlooked, sense that contributes to aesthetic pleasure. Tactile aesthetics refers to the sensory pleasure derived from physical interaction with objects, materials, and textures. From the cool smoothness of marble sculptures to the soft, plush embrace of a velvet cushion, touch plays a vital role in our understanding of beauty.

This dimension of aesthetics is perhaps most evident in the fields of product design and fashion. The texture of a handcrafted leather bag or the feel of a well-tailored suit can evoke a sense of refinement and luxury that is not merely visual but tactile. In architecture, the use of different materials—wood, concrete, glass—affects the way people experience and inhabit space, contributing to the overall aesthetic effect of a building.

Moreover, tactile aesthetics extends beyond human-made objects. The texture of natural surfaces, such as the rough bark of a tree or the softness of a flower petal, also invokes a deep aesthetic response. These tactile experiences, though subtle, often leave a lasting impact on our emotional and sensory well-being.

Case Study: The Aesthetics of Handcrafted Goods

The artisanal movement, which emphasizes craftsmanship and the tactile quality of handmade items, highlights the connection between touch and aesthetic value. The careful attention to detail in handmade pottery or woven fabrics not only reflects the skill of the artisan but also encourages a deeper, more intimate engagement with the object. By feeling the texture, weight, and form of an object, the viewer or user becomes more connected to it, experiencing beauty through the physical act of touch.

4. The Emotional Dimension: Aesthetics as a Catalyst for Feeling

Aesthetics is not just about pleasure, it’s also deeply entwined with our emotional responses. Art, literature, and even design have the power to evoke a vast range of emotions, from joy and wonder to sadness and nostalgia. It is in this emotional landscape that we begin to understand aesthetics beyond the visual and the immediate pleasure it provides.

Consider the feeling one might get when encountering a piece of art that tells a poignant story or reflects on themes of human suffering. The raw emotional power of a painting like Guernica by Pablo Picasso or a poem by Emily Dickinson can be as much a part of their aesthetic value as their formal qualities. These works are not merely beautiful in a visual sense; they resonate with us emotionally and invite us to engage with them on a deeper, more introspective level.

Case Study: The Aesthetics of Cinematic Experience

Film, as a medium, integrates visual, auditory, and emotional aesthetics into a single experience. Think of the emotional weight carried by a powerful film score, or the somber visual tones in a scene that evokes feelings of loss. A film like Schindler’s List uses both visual and auditory cues to elicit a profound emotional response. The aesthetic experience here is not confined to beauty in the traditional sense; rather, it encompasses an emotional journey that transcends the visual.

5. The Conceptual Dimension: Aesthetic Experience as Intellectual Engagement

Aesthetics is also closely related to the intellectual and conceptual realms. Not all aesthetic experiences are about pleasure, comfort, or emotional catharsis; many involve a deep intellectual engagement with ideas, forms, and structures. Conceptual art, for instance, often challenges the viewer to think critically, asking questions about the nature of art, culture, and society.

Aesthetic experiences can occur in the realm of philosophy, literature, and even in scientific exploration. The beauty of a mathematical theorem or the elegance of a scientific theory can invoke a sense of wonder and admiration that parallels traditional notions of aesthetic pleasure.

Case Study: The Aesthetics of Mathematics

One of the most striking examples of the conceptual dimension of aesthetics can be found in the world of mathematics. Mathematicians and scientists often speak of the “elegance” of a solution or the “beauty” of a proof. For example, the Pythagorean Theorem or Euler’s identity is celebrated not just for its utility, but for its inherent simplicity and symmetry. These concepts, while abstract, hold an aesthetic appeal that transcends their practical application.

6. The Future of Aesthetics: Multidimensional and Inclusive

As we move further into the 21st century, our understanding of aesthetics will continue to evolve. The digital age, with its virtual reality environments, immersive experiences, and artificial intelligence, has opened up new ways of experiencing beauty. Video games, virtual art galleries, and digital installations allow us to experience aesthetics in ways that blend the visual, auditory, emotional, and even interactive dimensions.

Moreover, as we become more attuned to the power of emotions, touch, and conceptual engagement, the aesthetics of the future will likely be more inclusive, reflecting a greater diversity of human experience. Aesthetic pleasure will no longer be confined to the visual or the immediately pleasant; it will encompass a broader, richer range of experiences that engage all of our senses, emotions, and intellect.

Conclusion: Embracing a Broader Vision of Aesthetics

In redefining aesthetics beyond visual pleasure, we unlock new dimensions of human experience. Aesthetic experiences are not limited to what we see; they are influenced by what we hear, touch, feel, and think. Whether through the sounds of music, the texture of a crafted object, the emotional power of art, or the intellectual stimulation of mathematical beauty, aesthetics can provide a profound understanding of the world around us.

By embracing this broader vision of aesthetics, we can appreciate the richness and depth of life in ways that transcend traditional ideas of beauty. Ultimately, aesthetics is about the way we engage with the world in all its forms, and the ways in which those experiences shape and enrich our lives.